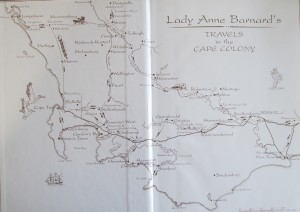

We set out in our Ford Ranger on the morning of Sunday May 10th intending to follow the route taken by Lady Anne Barnard in May 1798 as closely as possible. Time constraints, of course, meant that we were unable to stop at every farm; and in many cases both the road taken and the farm visited were no longer in existence or even identifiable.

We set out in our Ford Ranger on the morning of Sunday May 10th intending to follow the route taken by Lady Anne Barnard in May 1798 as closely as possible. Time constraints, of course, meant that we were unable to stop at every farm; and in many cases both the road taken and the farm visited were no longer in existence or even identifiable.

From Cape Town we took the N2 road over the Cape flats towards the Hottentots Holland Mountains, over the Kuils and the Eeerste Rivers, and past Meerlust Farm (near Stellenbosch) that had been in the Huisig family since 1693, at which Lady Anne had stopped. (An 8th generation of the Myburgh family now own and operate the farm (see Village Life 38 [Autumn 2010], 25-29 and 39 [Winter 2010], 24-29).

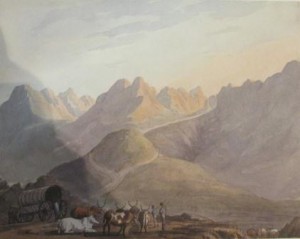

The wagon trails that Lady Anne would have followed had been established over centuries, first by game, then by indigenous peoples, and from the seventeenth century by European travelers such as Carl Peter Thunberg, François Le Vaillant, John Barrow, and William Burchell. One can still see remains of these trails going over Sir Lowry’s pass (Hottentot Holland Mountains), and the resemblance they bear to Lady Anne’s watercolour of the same.

Lady Anne’s observations reveal the same shrewd and ironic perspective that characterizes all of her writing:

“Hottentots Holland we found totally uninhabited by Hottentots, they poor things have been driven up the country by their avaricious masters, and nothing can better prove the grasping Hope of each individual to possess himself of large domains than the distance at which the settlers have placed themselves from each other …I think in Hottentots Holland there seemed to be a house and farm every mile or mile and a half—but no hamlet, no village.” (The Cape Journals, 305)

Coming over Sir Lowry’s Pass we dropped down into the lovely fertile fruit growing Elgin valley along the Steenbrass and the Palmiet rivers (“this last was the broadest River we had passed … I saw from the nature of the ground that it must be impassable after the Heavy rains” [307]) that Lady Anne followed to De Rust and Houwhoek, where she stayed on Sunday May 6th 1798. Despite Lady Anne’s disappointment at the establishment (“the room Mynheer Joubert received us in was bad enough”), she was happy to partake of the meal they were offered: “Being extremely hungry we ate up part of their dinner with them to which they had added some broiled fowls which with plenty of potatoes and good butter was a repast fit for an Emperor” (308). Dinner was so filling that Lady Anne declined to join the Jouberts for dinner, especially when she realized that the poor lamb she had seen tied up in the yard, was to be that dinner. “Poking into the Kitchen which I generally do, to make acquaintance with the Hottentots,” Lady Anne proposed letting the lamb go, but to no avail, for “Gaspar [their coachman] and the rest of the party shook their heads at that” (308). Indeed, Lady Anne seems herself to have succumbed to the temptation, as she remarks, with her usual ironic flourish, “Hide your diminished heads all ye French Cooks … never no never was there so good a pye tasted as that which contained the lamb” (308).

Houwhoek is now a hotel, and though people there knew nothing about Lady Anne, they were friendly and hospitable, and the walls of the hotel displayed framed extracts from Lady Anne’s diaries pertaining to her visit.

Houwhoek is now a hotel, and though people there knew nothing about Lady Anne, they were friendly and hospitable, and the walls of the hotel displayed framed extracts from Lady Anne’s diaries pertaining to her visit.

We saw none of the “the most brilliant everlasting flowers, pink, with blackhearts, [that] grew among the heath” (310) that Lady Anne remarks on in her dairy, but the valleys were spectacular (especially with the low cloud cover contrasted against the dark evergreens and the green mountainside) …

her dairy, but the valleys were spectacular (especially with the low cloud cover contrasted against the dark evergreens and the green mountainside) …

… and a small road side café we stopped at for a snack seemed to reflect the abundance of the neighbourhood.

… and a small road side café we stopped at for a snack seemed to reflect the abundance of the neighbourhood.

Lady Anne’s de Rust – Houwhoek encounter was typical of her experience throughout the journey in the Western Cape (and one that we, in our own way, shared). People were generally interested in her quest, and hospitable and even generous in offering food, lodging, conversation and information. Though she cannot resist a sarcastic remark when describing the house and the women of the house (whose physical corpulence Lady Anne seems to find a subject of endless amusement and remark), she also enjoys her time among the Dutch farmers, learns a great deal about their customs and farming practices, and strikes up friendships with men and women regardless of race. As she notes on leaving Houwhoek on the morning of May 7th.

“I felt myself better next day, begun a Friendship with Chanticleer, I mean my blue Woman who promises to to come to see us at the Castle… Mr. Barnard gave me a look to say no more… Mr. Barnard tells me I should get into terrible disgrace with the Quality of the Cape if a women so decidedly half cast or more, had been seen in the same room with them, no degree of beauty, manners or even fortune being sufficient to spunge off the Stigma of Slave born.” (309)

From Houwhoek our journey (like Lady Anne’s) took us down the N2 before taking the smaller original road down the Bot River valley toward Hermanus on the coast and up to Stanford. Like so many in this part of the Western Cape, the Bot River valley opens out into a sweeping fertile expanse bounded by mountains in the distance (in this case the mountains of the Babilonstoring and the Fernkloof Nature Reserve), spectacular, as one can see from the photos.

The Bot River valley looking NW and SE.

In making this descent the Barnard wagons almost sank in a marshy swamp, but as they approach the coast their ground is more secure and they are impressed by what they see.

“As we drove on we turned on our right to the mouth of the Bot Riviere, which empties itself into the Sea, at the foot of a long range of Mountains whose names I forget, and then to the left, rounding the Corner of a small neck of land which led us into another Bay which has no name that I can learn. A noble pool of water presented itself between us and the Sea on which there were plenty of wild ducks … the Bay to the right, some uncouth shaped hills to the left with a distant prospect of the mouth of the Clyne River and a sort of Peninsula which puts into the Sea made one of the finest scenes I had beheld.” (311)

We know now that the bay Lady Anne is unable to identity is the mouth of the Onrus River, near Sandbaai, and we can confirm that the “noble pool of water” that presented itself to her view soon afterwards, as they turned “left” (that is, north, up the coast), is Stanford lagoon, which is indeed lovely.

Because place names and landscape have changed over the last two centuries, we did not immediately realize that the elegant little town of Stanford was as closely connected to Lady Anne Barnard as we were to discover. It takes its modern name from one of its eminent citizens, Captain John Stanford (1807-77), who had served in the British army in Burma and in the Frontier Wars in the Eastern Cape (1835-36), who retired to this area in 1838 and bought the estate known as Kleine Riviers Valley. Although Stanford was ostracized by locals when he was forced to supply provisions to convict ships attempting to deliver convicts to the Cape, and was eventually ruined financially, the town was named for him in 1857, and his house exists today in the town centre. (https://portraitofavillage.wordpress.com/the-book/robert-stanford/).

Because place names and landscape have changed over the last two centuries, we did not immediately realize that the elegant little town of Stanford was as closely connected to Lady Anne Barnard as we were to discover. It takes its modern name from one of its eminent citizens, Captain John Stanford (1807-77), who had served in the British army in Burma and in the Frontier Wars in the Eastern Cape (1835-36), who retired to this area in 1838 and bought the estate known as Kleine Riviers Valley. Although Stanford was ostracized by locals when he was forced to supply provisions to convict ships attempting to deliver convicts to the Cape, and was eventually ruined financially, the town was named for him in 1857, and his house exists today in the town centre. (https://portraitofavillage.wordpress.com/the-book/robert-stanford/).

But when Lady Anne Barnard visited this area there was no such place as Stanford, and when she past the Klein [Clyne] River mouth and the Stanford Lagoon, she saw at a distance “an object of a different sort, a Handsome, English, Square built Country House close to the sea, round which I concluded I should see pleasure ground and Shrubberys in the same style” (311). This farm belonged to Hendrik Cloete, the owner of Great Constantia among other large estates, and one of the richest landowners at the time.

On closer inspection, however, Lady Anne found that the English country house she was expecting to find was no more than “4 miserable Slave Houses and farming Offices” and that the house itself was “two small rooms … and a nasty dark little Kitchen” (312). The Barnard party did not stay at Cloete’s farm (possibly called “Mondhuis” or Mossell River farm) but pushed on up the Klein River on a dangerous road in the dark until they reached what we assume to have been Klein River Valley farm, then owned by Christoffel Brand (who had loaned the Barnards his coachman, “the illustrious Gaspar”).

At Brandt’s farm they entered “thro’ a Kitchen filled with Slaves, many of them blessed with a very scanty portion of covering indeed” (315), a kitchen door that remains part of the house that we were fortunate to visit at 14 Church Street.

At Brandt’s farm they entered “thro’ a Kitchen filled with Slaves, many of them blessed with a very scanty portion of covering indeed” (315), a kitchen door that remains part of the house that we were fortunate to visit at 14 Church Street.

The present day Stanford House is owned by John Davies and Irene Stanford (no relation), who operate it as an antique shop, a second hand book shop, and a bed & Breakfast, welcomed us almost (we would like to think) as warmly as Brandt welcomed Lady Anne in 1798.

They were delighted to hear of our eccentric quest, of following in the footsteps of Lady Anne Barnard, but they were delighted in our interest in their home, and were happy to show us the kitchen door, the original rooms of the old eighteenth-century house, and the room in which, they think, Lady Anne slept in May 1798.

From Stanford we pushed on north following the Klein River and going through the Akkedis Pass. At this point of the afternoon we were concerned about getting to our evening destination, but we were also trying to follow Lady Anne Barnard’s route as best we could along the Klein River and cutting back behind the Kleinriviersberge past Teslaarsdal to the Hartebeest River and up to Caledon.

From Stanford we pushed on north following the Klein River and going through the Akkedis Pass. At this point of the afternoon we were concerned about getting to our evening destination, but we were also trying to follow Lady Anne Barnard’s route as best we could along the Klein River and cutting back behind the Kleinriviersberge past Teslaarsdal to the Hartebeest River and up to Caledon.

On this leg of her journey Lady Anne writes of a “quantity of Game … Partridges and Bucks chiefly” and the “Cockimacranki or what I shall call Hottentot pine apple” (316-7), but we saw none of this (if anything like is still to be seen) as we headed over gravel roads in our 4-wheel drive at 100kmph towards Teslaarsdal, where there was no sign of the “good farm belonging to one Teslar” [J.J. Tesselaar] or the “little clump of trees” (321) Lady Anne admired in the midst of a vast dusty plains and valleys, which you can see here in some photos of our road and others taken when we stopped for some refreshment on the road.

On this leg of her journey Lady Anne writes of a “quantity of Game … Partridges and Bucks chiefly” and the “Cockimacranki or what I shall call Hottentot pine apple” (316-7), but we saw none of this (if anything like is still to be seen) as we headed over gravel roads in our 4-wheel drive at 100kmph towards Teslaarsdal, where there was no sign of the “good farm belonging to one Teslar” [J.J. Tesselaar] or the “little clump of trees” (321) Lady Anne admired in the midst of a vast dusty plains and valleys, which you can see here in some photos of our road and others taken when we stopped for some refreshment on the road.

After losing our way several times on these small country roads, and scrambling the brain of the GPS system, we finally found our way past the Shaw Mountains, and onto the (relatively major!) road that would take us up to Caledon.

Our plan was to make it up to Greyton for the night, forty km north of Caledon, so that we would be poised in the morning to visit the Moravian Mission at Genadendal, a site of historic importance, which features prominently in Lady Anne’s travels. So while the Barnard party stopped in Caledon, we sped on by, still following their route as best we could on a small road that took us up the magnificent Swart River valley.

Our plan was to make it up to Greyton for the night, forty km north of Caledon, so that we would be poised in the morning to visit the Moravian Mission at Genadendal, a site of historic importance, which features prominently in Lady Anne’s travels. So while the Barnard party stopped in Caledon, we sped on by, still following their route as best we could on a small road that took us up the magnificent Swart River valley.

We arrived in the lovely village of Greyton an hour or so before sunset. We had found a quaint B&B, the Guinea Fowl, full of solid polished furniture, oriental rugs, and covered with wisteria, a house dating from about 1900, run by Jim and Muriel, a British couple who had been living in Southern Africa for 50 years, with fascinating tales to tell about the uprising in N. Rhodesia in the 1960s and WW II.

We arrived in the lovely village of Greyton an hour or so before sunset. We had found a quaint B&B, the Guinea Fowl, full of solid polished furniture, oriental rugs, and covered with wisteria, a house dating from about 1900, run by Jim and Muriel, a British couple who had been living in Southern Africa for 50 years, with fascinating tales to tell about the uprising in N. Rhodesia in the 1960s and WW II.

The warm afternoon gave way to the cool evening, and the autumn colors made one marvel at the richness that is this African landscape.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.