Our 4th day was our last following in the footsteps of Lady Anne Barnard in the Western Cape. From Tulbagh we planned to cut through Oudekloof Mountains, across the Klein Berg River, locate Leeuklip (in Saron), cut across to Darling and then up to Geelbek, on the Langebaan Lagoon, on the West coast. Lady Anne had stopped at all of these places. We then planned to return Cape Town after the rush hour traffic.

After breakfast the next morning we made our way to the Berg River and the “Roysand Pass” towards Saron. As Joanna Marx explains, before the area was named the “Land van Waveren” it was known as the Roodezand (“red sand”) valley, a name that still survives. There were no less than three passes from the Berg River valley into the Tulbagh valley, all known at some time as Roodezand” (Joanna Marx, “The Roodezand passes to the Tulbagh Valley,” VASSA Journal, 22 [Dec. 2009], 2-10).

After breakfast the next morning we made our way to the Berg River and the “Roysand Pass” towards Saron. As Joanna Marx explains, before the area was named the “Land van Waveren” it was known as the Roodezand (“red sand”) valley, a name that still survives. There were no less than three passes from the Berg River valley into the Tulbagh valley, all known at some time as Roodezand” (Joanna Marx, “The Roodezand passes to the Tulbagh Valley,” VASSA Journal, 22 [Dec. 2009], 2-10).

The trail taken by the Barnards in 1798 was reminiscent for Lady Anne of the mountain roads in her native Scottish Highlands and particularly challenging: “We … proceeded on to the Roysand Kloof, a very long and very bad pass which we were obliged to walk … it had much the resemblance of one of the roads thro’ the highlands of Scotland, having the banks of each side of the River which descended rapidly between them pretty well covered with bushes and different sorts of low wood “ (395).

According to Joanna Marx the trail taken by the Barnards was the Nieuwe Kloof, which “follows the course of the Klein Berg River in a narrow valley through the mountains, and various routes along it have been in use for two and a half centuries” (2). This pass, as Marx observes, “was made in about the 1750s and ran mainly along the northeastern side (right bank) of the Klein Berg River valley, very narrow in places, with two drifts …. Much later, Thomas Bain built his pass (1859-60) which went along the south-western side (left bank), and subsequently he built the railway (1873-74) on the same side. His road was widened in 1935 and can still be seen” (6). “The current Nuwekloof Pass (1968),” Marx observes, “runs on the north-eastern side (right bank), like the first route through this kloof. Now there are some high rock faces where the road is cut into the mountainside” (6).

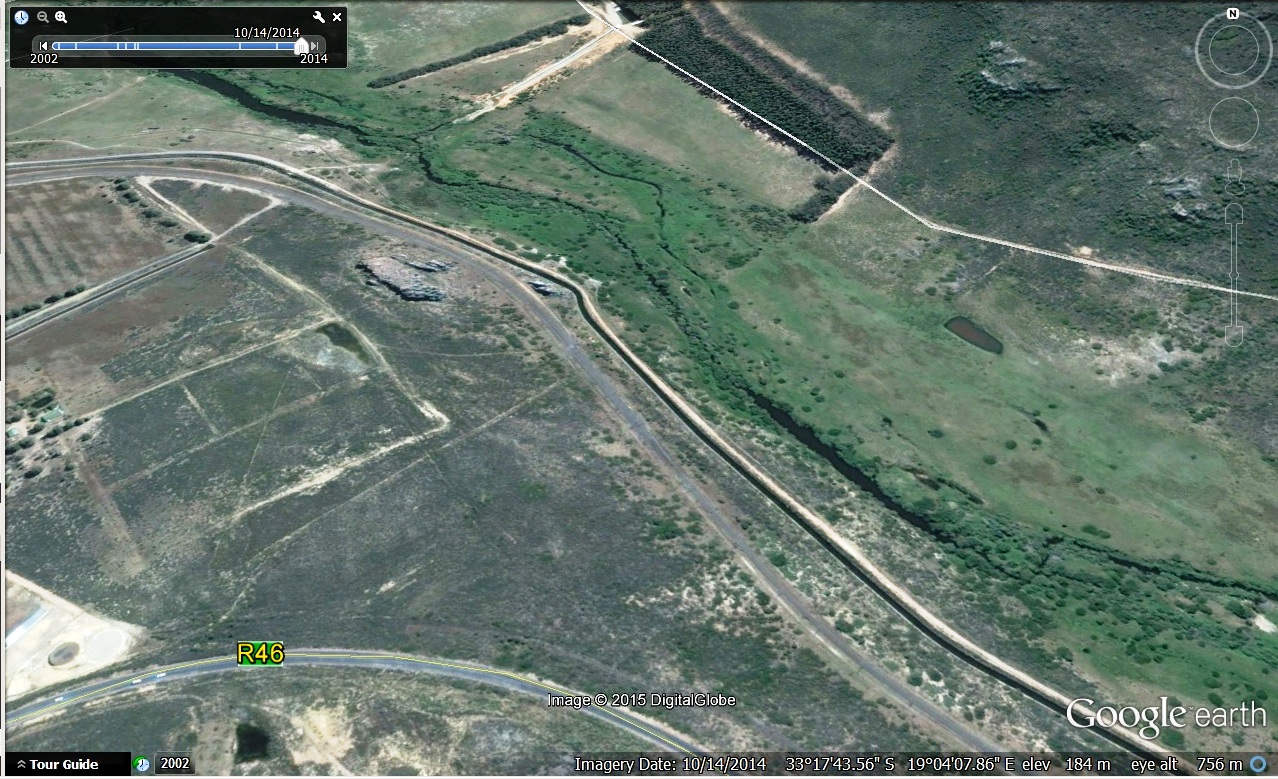

We consequently assumed that because the trail taken by the Barnards was inaccessible by car, the road we were taking in our car—R46 from Tulbagh to Saron past La Bonne Esperante—was not the trail taken by the Barnards. But when we re-examined where we had been, and looked carefully at the spot on Google Earth, we realized that our route through the Roodezand Pass had been almost exactly that of Lady Anne’s, and that without quite knowing it we had looked at virtually the same scene.

This is how Lady Anne describes the pass:

“We ascended Roy-sand Kloof, the waggon going slowly on before … the Road very bad, but romantic … as we reached the Summit the Sun was beginning to set with a glowing Orange ray to the left where he was retiring behind the hills, but where he still permitted us to see, and start at the Image which presented itself. A jet black Castle, turreted all round with a strange oddity of a Rock or building at a small distance, on the top of which was placed an enormous Urn which seemed to be the Sarcophagus of some Giant who had been Slain by the Prince of the Castle, who of course must have been the King of the Caffres by its sullen, dark appearance.” (395)

The image from Google Earth below identifies R46 that we took to Saron as well as the rocks that attracted Lady Anne’s attention, in the upper right quadrant of the image.

The two following are recent photographs (2010) of the same spot on the Roodezand Pass. They come from the blog of Trailrider—Adventures and Ride Reports, a self-styled “motorcycle enthusiast living in the Garden Route,” to whom we are grateful (http://trailriderreports.blogspot.com/2010/05/cape-mountains.html):

The two following are recent photographs (2010) of the same spot on the Roodezand Pass. They come from the blog of Trailrider—Adventures and Ride Reports, a self-styled “motorcycle enthusiast living in the Garden Route,” to whom we are grateful (http://trailriderreports.blogspot.com/2010/05/cape-mountains.html):

The following image, from Johannes Schumacher’s, The Cape in 1776-1777: Aquarelles by Johannes Schumacher from the Swellengrebel Collection at Breda (The Hague: A.A.M. Stols, 1951), depicts the view looking westwards from the Nuwekloof Pass, showing the features described in Lady Anne’s diary.

Lady Anne records the spectacular nature of the rock formation, and indicates that she too drew it: “I was grieved to hear that it had no History but was simply a production of Madam natures in one of her peaks, who was determined to throw out something to look like a work of art without Spade or Trowel having been used … I drew it, but have done it no justice” (395-96).

Lady Anne records the spectacular nature of the rock formation, and indicates that she too drew it: “I was grieved to hear that it had no History but was simply a production of Madam natures in one of her peaks, who was determined to throw out something to look like a work of art without Spade or Trowel having been used … I drew it, but have done it no justice” (395-96).

The following image of the Roodezand Pass is identified as Lady Anne’s in Lady Anne Barnard’s Watercolours and Sketches: Glimpses of the Cape of Good Hope (Fernwood Press, 2009), edited by Nicolas Barker (108-09).

Barker and Marx (9) both also draw attention to the fact that the same view of the pass, featured below, was drawn by Henry Salt in Twenty Four Views in St. Helena, the Cape, India, Ceylon, the Red Sea, Abyssinia, and Egypt (London: Henry Miller, 1809).

Barker and Marx (9) both also draw attention to the fact that the same view of the pass, featured below, was drawn by Henry Salt in Twenty Four Views in St. Helena, the Cape, India, Ceylon, the Red Sea, Abyssinia, and Egypt (London: Henry Miller, 1809).

Indeed, the Roodezand Pass rocks struck Lady Anne’s imagination deeply and she invented a story to go with them: “I’ll give it a History, write an Original Hottentot Song … translate it myself, put it to Hottentot musick & celebrate the fair maid confined by the Cruel giant in the dungeon of the black rock till rescued by her lover the Prince of the Caffres” (396). Indicative of enlightened views of the “Orient” and the exotic associated with it, Lady Anne sentimentalizes the scene and assimilates it to English literary genres (the gothic). But she also gives the indigenous people agency in this fantasy: the fair maid’s lover who rescues her is “the Prince of the Caffres.”

Indeed, the Roodezand Pass rocks struck Lady Anne’s imagination deeply and she invented a story to go with them: “I’ll give it a History, write an Original Hottentot Song … translate it myself, put it to Hottentot musick & celebrate the fair maid confined by the Cruel giant in the dungeon of the black rock till rescued by her lover the Prince of the Caffres” (396). Indicative of enlightened views of the “Orient” and the exotic associated with it, Lady Anne sentimentalizes the scene and assimilates it to English literary genres (the gothic). But she also gives the indigenous people agency in this fantasy: the fair maid’s lover who rescues her is “the Prince of the Caffres.”

We found Leeuklip in Saron without any difficulty. The contrast between this eighteenth-century Dutch farm and some of the others we had seen on our trip (e.g., The Oaks, Jan Harmansgat), was striking. Saron is a small, poor rural town, situated in a rather bleak and dust-blown landscape at the foot of the Saronsberg. Perhaps, as Michael D observed, its barrenness was partly due to the fact that the rains had not arrived yet. Certainly, Lady Anne compared the landscape of the rea in general to her native Scotland: “Nothing struck me remarkably on the road except the strong resemblance there is in the first part of the country we passed to part of Fife—lands carrying good corn, but there is little plantation… I saw no vineyards or Orange trees here …. Corn and cattle are the Chief commodities” (401).

However, Leeuklip is in a sad state of disrepair, its former beauties now barely recognizable. Mr. van Wijk (from the museum in Tulbagh) had told us that the farmhouse had once been used as the vicarage for the church nearby, where a Mission Station had been established by Johannes Heinrich Kulpmann in 1848 for the Rhenish Missionary Society. The church is still in use by the community as a Dutch Reformed Church, and the house and its outbuildings are used as a daycare centre and as a community centre for the elderly.

Lady Anne was impressed by what she found at Leeuklip.

“After travelling some miles more and passing the Lions rocks, so called from a fierce one having been killed there about 50 years ago, we reached the House of Myneer du Wal, a wealthy Man of rather a higher class than the other Boors, and one of the tallest Men I had seen. He and his Wife welcomed us with cordiality, a tall daughter was of the party who looked rather older than her Mother, a very good looking Brother, but a cub, and a youngish looking tall Man in a calico powdering gown, with a great deal of manner who talk’d Dutch but looked so like a French Man and like the late Prince Louis D’Aremberg that I could by in means translate him… We slept this night in the best furnished and handsomest room we had yet been in, both the beds had curtains and every bed 4 … there was magnificence but our glass still required a Chair to mount up to … ” (396)

The sketch below by Lady Anne may be of Leeuklip. As Nicolas Barker observes, “Perhaps this is an archetypal homestead based on others seen by Lady Anne during their journey. The Barnards stayed at several large, well-established farms between Roodezand and Saldanha Bay, including Leeuklip, with the de Wal family, and Theefontein, with the Slabbert family” (110).

The photo below is provided by Mr. van Wijk: “probably taken in the first two decades of the 20th century, showing the front façade of the building and some school / Sunday school children.”

The photo below is provided by Mr. van Wijk: “probably taken in the first two decades of the 20th century, showing the front façade of the building and some school / Sunday school children.”

The architectural details of the present Leeuklip (see below), especially the stable door with fanlight and the decorative gables at the front and side of the house, suggest strongly that Lady Anne’s sketch above is indeed Leeuklip. Compare (below) details of the gable (front and side) and of the wall from Lady Anne’s sketch and from our photos.

At Leeuklip people wondered at our interest in Lady Anne Barnard—indeed, they had never heard of her—but they welcomed us warmly, engaged us in conversation, showed us some of their embroidery work, talked about the financial difficulties of living in Saron and of maintaining the old house, showed us the church, and allowed us to look around and to take photographs.

Though the historic core of the Saron Mission Station was declared to be a provincial heritage site in 2013, there was little left of the original interior—perhaps a doorway, and a lock on a door; little else.

After an interesting and somewhat melancholy hour we took our leave of the old folks at Leeuklip, stopping to look back at the old house from across the rather grim uncultivated field.

After an interesting and somewhat melancholy hour we took our leave of the old folks at Leeuklip, stopping to look back at the old house from across the rather grim uncultivated field.

The Barnard party visited other farms in the area—in the company of du Wal, for example, they visited Gelukwaard, the farm of Christoffel Leiste, and they found this “a most confortable looking place—plenty of trees—a good garden … All looked wealthy and flourishing here” (398). We were pressed for time, and did not turn in the direction of Gelukwaard (which apparently still exists, and was visited in 1990 by Jose Berman). Instead we headed out over a rather bleak Swartland country towards Darling.

Apparently, the Barnards stopped at Theefontein, near modern day Darling, the home of Johannes Slabbert (who was away from home when they arrived, though at home when they stopped at Theefontein on their way back to Cape Town). At Theefontein Lady Anne remarks on the giant stature of the inhabitants, and is impressed by an old lady of 77 years of age and by “12 to 18 favourite Cats who breakfasted with her every morning and do not appear till next day but hunt for themselves amongst the low bushes, they were very beautiful ones indeed” (402-03). Lady Anne drew the old lady, leaving the original for her daughter—who called Lady Anne “a lieve Vrouw … a dear Lady” (403)—and taking a copy for herself.

Perhaps it is because the old lady and her cats make Lady Anne think of her cousin Anne Keith and her cats, that Lady Anne at this point reflects on the readers of her journal and why she keeps on writing: “Nothing I am sure but the attachment in my heart to those whom I expect will read this Manuscript with pleasure because it is mine could have made me continue to write day after day, locking myself up in my apartment that I may not be interrupted and that the garrison may not see what I am about and quiz me for a Journalist … but it is so sweet to think that tho’ far away I am living with you all … that at this moment while addressing those who I need not particularize for their hearts will tell them who I mean, my pages are read with a softened eye and I am almost looking direct in the face of my Reader and saying God bless you!” (404).

I am unable to find a reproduction of the sketch of the old lady. The following is a sketch of “a grandmother” she took on her visit to Ganzekraal, near present day Grotto Bay, a coastal resort half way between Cape Town and Saldanha Bay, just south of Geelbek.

From Theefontein the Barnards made their way to Stompe Hoek (modern day Langebaan), over difficult sandy terrain, and then to Geelbek, where they were met by the Postholder, Jacobus Stofberg. She says, “We saw no cultivation here or any other foliage but sea plants, the season of flowers being over there were scarce any traces of them to be seen but at the proper time of the year … viz. the months of Sept and October I was told the profusion of beautiful ones pass idea, are charming, everlasting of brightest pink and most delicate form“ (405).

From Theefontein the Barnards made their way to Stompe Hoek (modern day Langebaan), over difficult sandy terrain, and then to Geelbek, where they were met by the Postholder, Jacobus Stofberg. She says, “We saw no cultivation here or any other foliage but sea plants, the season of flowers being over there were scarce any traces of them to be seen but at the proper time of the year … viz. the months of Sept and October I was told the profusion of beautiful ones pass idea, are charming, everlasting of brightest pink and most delicate form“ (405).

Though we can find a Lady Anne sketch of Ganzekraal, we can find none of Geelbek Farm, now a restaurant (http://geelbek.co.za/new/), positioned, with a number of outbuildings and old ancient walls, on the southern shore of the Langebaan lagoon.

Though we can find a Lady Anne sketch of Ganzekraal, we can find none of Geelbek Farm, now a restaurant (http://geelbek.co.za/new/), positioned, with a number of outbuildings and old ancient walls, on the southern shore of the Langebaan lagoon.

Though they slept “but moderately” (406) at Geelbek, “the day being a fine one, [they] proposed going to the Out Keck [Uitkyk], or look out post, about four miles distant to see the Bay and adjacent country from the highest ground” (407-08). Saldanha Bay, about 70 miles north of Table Bay, is a naturally excellent harbor that attracted interest from colonial powers and saw two important battles in Lady Anne’s time, in 1781 and 1796, the last of which saw the British triumph over the Dutch to establish their jurisdiction at the Cape Colony (in 1806 the British triumphed again in a battle against the Dutch at Blaauwberg, a place at which the Barnards picnicked on their way back to Cape Town, some miles south of Langebaan; this battle issuing in British rule of the colony until 1961). Geelbek is at the southern end of Langebaan lagoon, which in turn is at the southern end of Saldanha Bay, as may be seen from the detail of an eighteenth-century map below (in Tulbagh Church). The Barnards spent their time on the lagoon, and did not venture as far as Saldanha Bay itself.

On their walk from Geelbek they enjoyed the “fragrant … Aromatic scent of many of the wild shrubs which grow here in profusion: (408).” Vlaeberg is the highest point in Saldanha Bay (633 feet), on the eastern side of the peninsula, and here Lady Anne sketched the landscape, about which she reflected: “I sat down on a Stone and endeavoured to take a sort of Panorama view of the place which my position on this high ground rendered easy, the young Ladies sat down on a another and fell to their reveries, while I went on with mine…. My first was to look round the wide extended prospect with wonder at my being here at all” (408).

On their walk from Geelbek they enjoyed the “fragrant … Aromatic scent of many of the wild shrubs which grow here in profusion: (408).” Vlaeberg is the highest point in Saldanha Bay (633 feet), on the eastern side of the peninsula, and here Lady Anne sketched the landscape, about which she reflected: “I sat down on a Stone and endeavoured to take a sort of Panorama view of the place which my position on this high ground rendered easy, the young Ladies sat down on a another and fell to their reveries, while I went on with mine…. My first was to look round the wide extended prospect with wonder at my being here at all” (408).

What Lady Anne drew may be the image below, which she titled “Johnsons Bay,” which (Nicolas Barker suggests) may be a reference to Commodore George Johnstone, whose squadron captured the VOC fleet in Saldanha Bay during the 4th Anglo-Dutch War in 1781 (113).

We, however, did not see landscape resembling the coastline represented by Lady Anne in this sketch, though we too looked with “wonder” at “a wide extended prospect,” suggested by the pictures below.

We, however, did not see landscape resembling the coastline represented by Lady Anne in this sketch, though we too looked with “wonder” at “a wide extended prospect,” suggested by the pictures below.

Back at the Nieuwe Post (Geelbek) the Barnards found dinner ready and Lady Anne was delighted that Stofberg’s son had shot two flamingoes for her, like the birds we had photographed, today protected by government ordinance. One was dead, and one had been wounded in a wing. Lady Anne “formed a hope of his living to be the wonder and delight of all my Friends in old England” (411), but after some moralizing about preferring to keep the bird alive rather than to put it out of its misery, she is persuaded to leave it behind with the Stofbergs.

As Lady Anne’s month-long travels began to draw to a close, after what had clearly been a very rich and informative experience, she reflects ruefully on what feels to her like an absence of knowledge, a limitation:

“I begun to regret that I have not read any of the accounts of the Cape before I wrote this little Tour. I wished to keep myself free from prejudice or plagiarism, to follow my own style and express myself in my own way, which I should have inadvertently departed from to adopt any thing else that I had liked better, the consequence is that I have not had the proper knowledge of many simple points necessary to set off from , and that my Journal is far less accurate , intelligent, or specious as to wisdom than it might have been had I copied from Journals already written, what in reality I ought to have copied.” (409)

Though other eighteenth and nineteenth-century travellers in the Western Cape have been better informed than Lady Anne Barnard, with more geographical, historical, and political knowledge, there is nonetheless an intellectual honesty in recognizing the limitations of her experience in this strange and new land—however much like the county of Fife it sometimes seemed to her to be—while she also embraced its newness and challenges. Having followed in Lady Anne’s footsteps for about 1000 kilometers, as best we could, and having seen many of the places that she had seen, we have been delighted and instructed by the freshness and the insight of her account, and we would not have exchanged hers for the views of another. As she says of herself: “I put down most truly all I saw, and that was only Sea, rock, mountain and heath or underwood far as the eye could reach.”\

Our afternoon at Geelbek was spent in a leisurely fashion. We explored the old house itself—tracing the story of its history and its owners from 1786 in documents, maps, and family trees decorating its walls, and learning about its restoration in the twentieth century (bought up in 1987 by the South African Nature Foundation) and its status as part of a West Coast National Park area dedicated to preserving the ecology and environment of this wild and wonderful part of the coast. We explored the outbuildings, many of which would have been here—in earlier incarnations—when Lady Anne visited.

With quiet pleasure we watched the flamingoes and other bird life from the “blind” on the lagoon.

We enjoyed an excellent late lunch at the restaurant (at which we were then virtually the only customers), having an interesting conversation with the owner about her art collection.

Then we set off back to Cape Town, by a more direct route than the Barnards, satisfied by our short but very engaging adventure in the footsteps of Lady Anne Barnard.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.