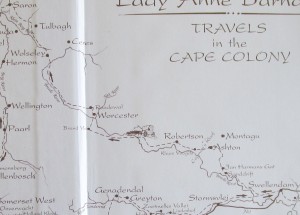

On day three of our journey in the footsteps of Lady Anne Barnard in the Western Cape we planned to move fairly quickly along the slopes of the Langeberg, through the Breede River Valley, from east to north west, past Ashton, Robertson, Worcester, Wolseley to Tulbagh, where we had an appointment with Mr. Calvin van Wijk, the manager of the Oude Kerk Volksmuseum.

Like Lady Anne we stopped at Jan Harmsgat, a fine Dutch farmhouse dating from 1723, and (like The Oaks) now a working farm that offers luxury dining and accommodation (http://www.janharmsgat.com/index.php). We were kindly received, but those running the farm now knew little about Lady Anne Barnard—here there was no local lore or inherited story about Lady as there were in other places—and after looking around the magnificent estate and house, we were on our way.

Like Lady Anne we stopped at Jan Harmsgat, a fine Dutch farmhouse dating from 1723, and (like The Oaks) now a working farm that offers luxury dining and accommodation (http://www.janharmsgat.com/index.php). We were kindly received, but those running the farm now knew little about Lady Anne Barnard—here there was no local lore or inherited story about Lady as there were in other places—and after looking around the magnificent estate and house, we were on our way.

We were unable to locate the farm of Pieter du Toit, Roodewal, near modern day Worcester, where Lady Anne was well received and “agreeably surprised with a cleanliness as singular as the contrast we had lately quitted, the Staffordshire plates in the inside of their glass Cupboard shone bright, having been well wiped with a clean cloth, no greasy nightcap … the brass spoons & ditto tea and Coffee urns were polished as looking glasses” (390).

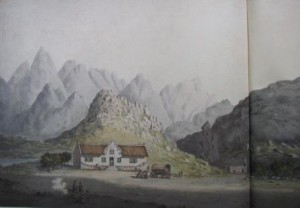

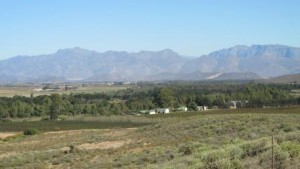

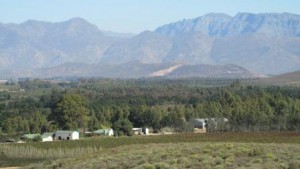

Lady Anne attempted to capture the starkness of the geographical location of du Toit’s farm: “What a noble near Mountain, what a nobler distant one, composed of Spiral forms like a Cathedral, and what a capital rock as a fore ground … Trees were wanting but as Margaret would say ‘the bones of the country’ were charming” (389-90).

Lady Anne attempted to capture the starkness of the geographical location of du Toit’s farm: “What a noble near Mountain, what a nobler distant one, composed of Spiral forms like a Cathedral, and what a capital rock as a fore ground … Trees were wanting but as Margaret would say ‘the bones of the country’ were charming” (389-90).

Detail of Pieter Du Toit’s farm “Roodewal” in the Breede River valley

Detail of Pieter Du Toit’s farm “Roodewal” in the Breede River valley

As we drove on through the Breede River Valley we were able to see and appreciate the extraordinary landscape that stretched as far as the eye could see and that impressed Lady Anne: “The farther we proceeded thro’ the Valley the more bold and picturesque became the Mountains, their form more varied and striking than any I had seen before. These as usual were succeeded by others—and others” (389).

As she drove west Lady Anne “soon crossed the Riviere for the 3rd time, and entered upon the Country called Roysand, or red sand …. After travelling about four hours, we crossed a pretty deep tho’ narrow riviere and stopped at a farm House of good size where Mynheer Prince told us we should dine. Nom invitation on such occasions is necessary from the Farmers, when a Waggon stops at the door he concludes of course that the passengers want to Scoff (to eat) and the Horses the same after they have rolled themselves … here we fell in exactly with the diner hour, 12 o’clock …” (394). And although Lady Anne is often sarcastic about the quality of the food she receives (“to be sure a very greasy one, dressed after the right Dutch fashion” [394]), she also expresses her appreciation for the generosity of the Dutch farmers—“to say the truth I find all this class of people very hospitable and I hear they are equally so to others who they may be supposed to have less interest in obliging” (395).

It is unclear, however, exactly where they stopped in relation to the present day town of Tulbagh, which they certainly visited en route to the de Waal’s farm Leeuweklip (in modern day Saron), which Lady Anne does identify, and which we visited the day after. Because the names of mountains passes, farms and villages have changed over the years, we were sometimes flying in the dark.

Tulbagh is a beautiful old town in the wine lands of the Western Cape, surrounded by mountains, graced with many fine, old Dutch buildings, and a town that attracts visual and performing artists, wine connoisseurs, and visitors from far and wide. Though the town was named for Cape governor Ryk Tulbagh (1699-1777) in 1795, its general area was initially known to Europeans as the “Land van Waveren” after a Dutch family related to the first Dutch governor Simon van der Stel, and then as Roysand Kloof, the term Lady Anne uses in her diaries. Roysand had been cultivated by settler farmers in the early eighteenth century, and by the early nineteenth century had acquired many notable civic and domestic buildings—such as the church (1743), the Drostdy (1804), the old library, and private Dutch houses on Church Street. Many of these were destroyed in an earthquake of 1969, and subsequently rebuilt and restored to their original splendour (http://www.heritageportal.co.za/article/ashes-south-africas-worst-earthquake-rise-old-buildings-tulbagh. For a list of heritage sites in Tulbagh today see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_heritage_sites_in_Tulbagh).

In Tulbagh we met with Mr. van Wijk at his office in the museum, and after a long discussion about genealogy and local history (on which Mr. van Wijk is an expert), he gave us a long, informed and fascinating tour of the Church, which had been the centre of the town in Lady Anne’s day, and its contents.

In Tulbagh we met with Mr. van Wijk at his office in the museum, and after a long discussion about genealogy and local history (on which Mr. van Wijk is an expert), he gave us a long, informed and fascinating tour of the Church, which had been the centre of the town in Lady Anne’s day, and its contents.

There is actually no statement in Lady Anne’s diaries that they visited the church in Tulbagh (Roodezand). But since they went to Roodezand, and since the church was one of the main buildings, they probably did visit it, and attend a service there, as they did in other locations on this trip. Mr. van Wijk pointed out the architectural changes of the church since the 1790s (when the entrance was in a different position, in what is now the south transept — see below right).

And we admired the old ornate lectern that had been operational in Lady Anne’s day, and from which she might have heard a sermon.

Mr. van Wijk was also helpful in explaining to us the continuing existence of Leeuwklip (in modern day Saron), resorting to google earth to identify the old farm for us. We were having difficulty identifying the mountain pass used by the Barnard party to reach Leeuwklip, given that the passes from Roodezand (Tulbagh) to Leeuwklip (Saron) had changed during the nineteenth century, and we discussed the various possibilities that have subsequently been clarified for us by an article on the Roodezand Pass by Joanna Marx in the VASSA Journal (Vernacular Architecture of South Africa) that Michael D found online (more about this tomorrow).

We are grateful to Mr. Wijk, as we are to others on this trip, who took hours out of his work day to share his extensive local, historical knowledge and enthusiasm with us.

The Drostdy in Tulbagh, which (unusually) was built a little distance outside of the town, is of slightly younger date than the Church and would not have been known to Lady Anne, but we decided to have quick look at it, and at a couple of mid-eighteenth century cottages that would have been there at the time of Lady Anne’s visit.

The Drostdy in Tulbagh, which (unusually) was built a little distance outside of the town, is of slightly younger date than the Church and would not have been known to Lady Anne, but we decided to have quick look at it, and at a couple of mid-eighteenth century cottages that would have been there at the time of Lady Anne’s visit.

In the late afternoon sunshine we strolled along the remarkable Church Street in Tulbagh—looking a little like a Hollywood set, in its perfection, but feeling also very real and immediate—admiring the many eighteenth and nineteenth-century Dutch houses, reading the architectural notes for each of the homes, and chatting to the residents and some workmen restoring one of the older buildings.

One of the great instructional pleasures of Tulbagh was our lodging for the night—The Cape Dutch Quarters (http://www.cdq.co.za/), on Church Street, dating from 1809, a portfolio of heritage properties now converted for use as a guest house. Our home for the evening was a spacious, comfortable, old fashioned guest house with solid, traditional furniture, works of art and antiques in every room, four-poster beds with deep soft linens, a large dining table at which we were served a sumptuous breakfast, private gardens and courtyards, and a swimming pool (apparently closed for the season, but too tempting for the visitor from the northern hemisphere to resist.

This being the autumnal off-season, we were the only guests in the whole house.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.