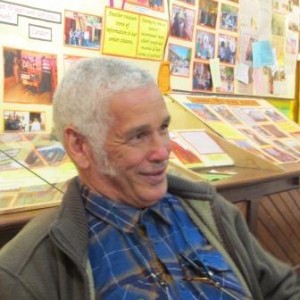

On Monday May 11th we met Dr. Isaac Balie at 10 am in the square of old Genadendal, a few miles from Greyton.

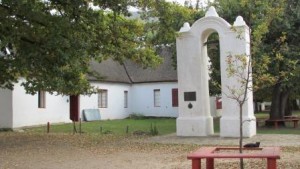

Genadendal is one of several places in the Cape settled by the Moravians in the eighteenth century. Known then as Baviaanskloof, the Herrnhuters’ mission was established by Moravian Georg Schmidt in 1737 (abandoned in 1744 and re-established in 1792) to convert the indigenous people to Christianity.

After 50 years Dr. Isaac Balie has just retired as director of the Genadendal Mission Museum, whose present existence as a world class living history museum is almost entirely due to his passion, knowledge, and commitment, sometimes under difficult financial and political circumstances. (The museum’s facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/GenadendalMissionMuseum?fref=ts)

Dr. Balie is a gentle, generous and humorous man of wide knowledge and an easy and communicative disposition. Over coffee we talked for an hour about Lady Anne Barnard’s time in Baviaanskloof, about the recent history of the museum, and his continuing vision and hope for the site and the history it represents. We were touched by Dr. Balie’s humane reflectiveness — and by his reciting from memory passages from Lady Anne’s diary.

Dr. Balie is a gentle, generous and humorous man of wide knowledge and an easy and communicative disposition. Over coffee we talked for an hour about Lady Anne Barnard’s time in Baviaanskloof, about the recent history of the museum, and his continuing vision and hope for the site and the history it represents. We were touched by Dr. Balie’s humane reflectiveness — and by his reciting from memory passages from Lady Anne’s diary.

He showed us the various buildings known to be associated with Lady Anne – the chapel at which she attended a church service and the room in which she slept.

He also showed us an original woven Koi mat used in the Church, a sample of which was given to Lady Barnard, a pear tree and a Chinese rose bush locally associated with Lady Anne (of which we can find no mention in her diary).

Taking advantage a warm sunny morning, we walked through the environs of the historic mission station, Dr. Balie showing us his lemon trees, the remnants of a Koi camp dating from the eighteenth century, and the graves of the three clergymen who welcomed Lady Anne to Baviaanskloof.

Taking advantage a warm sunny morning, we walked through the environs of the historic mission station, Dr. Balie showing us his lemon trees, the remnants of a Koi camp dating from the eighteenth century, and the graves of the three clergymen who welcomed Lady Anne to Baviaanskloof.

Lady Anne had undertaken to provide certain kinds of pragmatic information to officials at the Cape and to the government minister Henry Dundas: “What I have endeavoured and shall endeavor to do is to give the topographical account of all I see cultivated for you mon cher ami Monsieur Dundas… Africa is your Masters Villa (George the 3rd)” (320). But in Genadendal Lady Anne was struck by a different kind of cultivation. She is moved to write with unusual warmth and admiration of the simple spirituality that she witnessed among both Moravians and Hottentots at the mission.

She acknowledges that “the Fathers, or Hern Hutters … as they are called in this Country, were no favourites of their [the farmers], and eer long we shall see the reason” (327). She is impressed by the Moravians: “The Fathers of whom there were three, came out to meet us in their working Jackets, each Man being employed in following the business of his Original profession—a Miller … a Smith …a Carpenter and Taylor in one.—There, but apart from that, unity seemed to be Equality. They welcomed us simply and frankly, without artificial gladness, or more than hospitable civility…” (329).

She acknowledges that “the Fathers, or Hern Hutters … as they are called in this Country, were no favourites of their [the farmers], and eer long we shall see the reason” (327). She is impressed by the Moravians: “The Fathers of whom there were three, came out to meet us in their working Jackets, each Man being employed in following the business of his Original profession—a Miller … a Smith …a Carpenter and Taylor in one.—There, but apart from that, unity seemed to be Equality. They welcomed us simply and frankly, without artificial gladness, or more than hospitable civility…” (329).

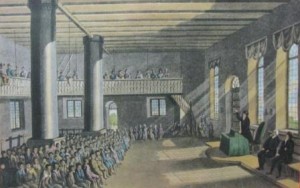

Lady Anne learns the history of the Moravians from the three clergymen and was able to acquire a good sense of the primitive and simple nature of the Moravian community at Baviaanskloof: “the House we were then in, was built with their Own hands five years ago … their object was to Convert the Hottentots, to render them industrious, religious and happy” (330). She is shown the old church by the Fathers, a room 40 by 20 feet whose floor is covered by “rush matts of a sort of reed” (of the kind shown to us by Dr. Balie), a room in which “the pulpit was only a few steps, raised above the ground and matted with the same rushes on which chairs placed and a small Table and desk on which was the Bible… The Church had benches on each hand, the right side for Men, the left for Women and to these they entered by separate doors, at the end” (330).

Though Lady Anne arrives on a Thursday and not a Sunday, when she would have seen 300 at Church, she nonetheless attends a smaller service, and is impressed by what she sees:

Though Lady Anne arrives on a Thursday and not a Sunday, when she would have seen 300 at Church, she nonetheless attends a smaller service, and is impressed by what she sees:

“I doubt much whether I should have entered St. Peters at Rome with the Triple Crown itself present in all its Ancient splendor with a more awed impression of the deity and his presence than I did this little Church of a few feet Square, where the simple disciples of Christianity dressed in the Skins of Animals knew no purple or fine liner, no pride … no hypocrisy. I felt as if I was creeping back 1700 years, to hear from the rude but inspired lips of Evangelists the simple sacred words of wisdom and purity.” (330-31)

The power of the service is enhanced for Lady Anne by the “deep toned Bass” and the “excellent harmony” of “the Fathers,” and “about 150 Hottentots joined in the 23rd psalm in a tone so sweet, so loud, but so just and true that it was impossible to hear it without being surprised” (331). Lady Anne laments her limited understanding of Dutch, as the preacher expounds a portion of Mathew chapter 8, verse 11, but “a word now and then I knew the subject he dwelt on, that the goodness of God knew no distinction of persons, and that the Dutchman who was great and rich, with abundance of Slaves and Cattle, was not more sure of a place in a better world which after death we should go to than the Hottentot who was good, and who would find a seat in Heaven kept for him to eternal happiness…. Not a Hottentot did I see in this congregation that had a bad passion in the Countenance, I watched them closely, all was sweetness and attention. I was even surprised to observe so few vacant eyes, and so little curiosity directed to ourselves… ” (331).

Fanciful as it may be, we remarked on how like these old Moravians Dr. Balie was in the simplicity, directness and energy of his pursuits and discourse. We found ourselves reading a passage of Lady Anne’s Diary with Dr. Balie in the market square, captured by Michael D on one of his various cameras.

We had seen the Chinese rose, the pear tree, and the early nineteenth century Wagon – one that had been used by Christian LaTrobe (1758-1836), the English Moravian minister, when he travelled through Genadendal in 1815-16, very like the Wagons used by the Barnard party in 1798. But we had heard nothing about the gift Lady Anne had given to the community.

Persuaded by the Moravian clergymen not to give material objects of a superficial kind to the local people, Lady Anne alights on something special that she thinks would benefit all and that pleases the Moravian clergymen:

Persuaded by the Moravian clergymen not to give material objects of a superficial kind to the local people, Lady Anne alights on something special that she thinks would benefit all and that pleases the Moravian clergymen:

“The present of all I put most value on, and which they seemed to value most, was the 3rd part of the Fleshy Margaret Strawberry … fond of their Garden, and extremely neat in the divisions of it, I pointed out how delicious this fruit would prove if well taken care of and that it was sent me by my Sister Margaret, the most beautiful woman in Europe, who desired it might be called by her own name, and ‘you, fathers’ said I, ‘are the only people in Africa who have this.’… The circumstance pleased them, even under the Bavian Kloof a pretty woman is not without her influence in creating the glow of vanity in a holy heart …” (334)

This gift of a strawberry plant was news to Dr. Balie. We agreed there was unlikely to be any trace of the plant after more than two centuries, and we agreed on the liveliness and wit of Lady Anne’s account of people and places.

This gift of a strawberry plant was news to Dr. Balie. We agreed there was unlikely to be any trace of the plant after more than two centuries, and we agreed on the liveliness and wit of Lady Anne’s account of people and places.

After a lovely sunny autumn morning with Dr. Balie, full of interest and information, we set off on a secondary gravel road in the direction of Riviersonderend (“river without end”). We knew that Lady Anne had stopped at a place called Zoetmelks Vallei (Sweet Milk Valley), site of an early British settlement, and at other farms, Het Ziekenhuys (later known as Nethercourt) and Lindeshof. Dr. Balie suggested that Zoetmelks Vallei was also called or associated with The Oaks, and that The Oaks continued as a thriving concern.

We set off in expectation.

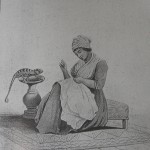

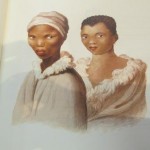

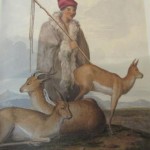

Below are some drawings of local people done by Lady Anne in Genadendal.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.