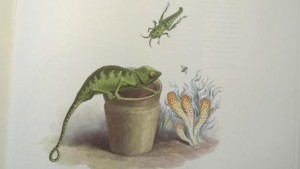

In May 1798, after a year at the Cape Colony as the colonial secretary under Sir George Macartney, Andrew Barnard and his wife Lady Anne Barnard traveled into the interior of the colony (on a kind of working vacation), and Lady Anne’s diary account of the experience offers some fascinating insights into the life, culture and landscape of the Western Cape at the end of the eighteenth century, while also revealing much about Lady Anne’s personality – her intelligence, wit, modernity, and ability to capture the essence of place and person in a few words or in one of her lambent watercolours.

My plan is to follow, as best one can in a few days and under greatly changed circumstances, in the footsteps of Lady Anne in the Western Cape (and later, up Table Mountain). An old friend, Michael D (a man with deep local knowledge), and I have mapped out a route that will take us on a circuitous, yet vaguely circular journey, from Cape Town to Caledon, Stanford, Greyton, Genadendal, Swellendam, Robertson, Tulbagh, Langebaan, Darling, and back to Cape Town.

We plan to call at a number of eighteenth-century farms visited by Lady Anne and her party, to see some of what she saw there in both town and country; to learn what we can about her observations and activities at the eighteenth-century Moravian Mission of Genadendal; and to visit the Drostdy in Swellendam and the old Dutch quarter in Tulbagh – both still bearing traces of their eighteenth-century past – both the object of fascinating comment in Lady Anne’s diaries. (“Drostdy,” according to Miriam-Webster, is an Afrikaans word for “the office or residence of a landdrost,” the local squire or landowner, or “the jurisdiction of a landdrost”).

We plan to call at a number of eighteenth-century farms visited by Lady Anne and her party, to see some of what she saw there in both town and country; to learn what we can about her observations and activities at the eighteenth-century Moravian Mission of Genadendal; and to visit the Drostdy in Swellendam and the old Dutch quarter in Tulbagh – both still bearing traces of their eighteenth-century past – both the object of fascinating comment in Lady Anne’s diaries. (“Drostdy,” according to Miriam-Webster, is an Afrikaans word for “the office or residence of a landdrost,” the local squire or landowner, or “the jurisdiction of a landdrost”).

The Barnards, of course, traveled by horse and ox wagon crossing mountains – the Overberg and parts of the Franschhoek Mountains – and rivers that could have been (and sometimes were) raging from the autumnal rains. When we set out on May 10th we will rely on an old Ford Rangler and modern maps, and though this mode of transportation does not offer the same immediate contact with the natural environment or with local people as the Barnards had, we plan to use small, sometimes uncharted country roads (where the sat-nav and GPS have little sway), and to seek Lady Anne stories from farmers, landowners, and museum folk as we encounter them.

This bird shaped pool in Kirstenbosch Gardens was, for many years, known as Lady Anne Barnard’s bath. In fact, it was built by Colonel Christopher Bird, the deputy colonial secretary, in 1811, and thus was unknown to Lady Anne. But the persistent association of the pool with Lady Anne suggests her continuing half-mythical stature at the Cape.

This bird shaped pool in Kirstenbosch Gardens was, for many years, known as Lady Anne Barnard’s bath. In fact, it was built by Colonel Christopher Bird, the deputy colonial secretary, in 1811, and thus was unknown to Lady Anne. But the persistent association of the pool with Lady Anne suggests her continuing half-mythical stature at the Cape.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.